Pete, or James K. Stepro, as was his given name, was born on a chilly February Saturday in 1912. The seventh of eight children in a three-room house with no electricity, he was from inauspicious beginnings. The family was poor but they did the best they could. His early years were full of joy, with his siblings and cousins around to play with and entertain the precocious child. All of them would even scrounge up a nickel a piece to go down to the Dream Theater every Saturday to watch the silent movie that was playing. Then on Sundays, they trudged to the First Methodist Church for worship services.

Pete, below at age 4, was doted upon.

Even from a young age, it was clear that Pete was a strong character – one that was born to lead. He dealt with adversity in a calm manner, one that impressed his teachers early on. And, like many in his generation, he had to learn to be the man of the house at a young age. In 1926, when Pete was just 14, his father died. Immediately, Pete knew his dreams of graduating high school would have to be cast aside so that he could provide for his family. He dropped out of the 8th grade and took a job delivering milk.

Even from a young age, it was clear that Pete was a strong character – one that was born to lead. He dealt with adversity in a calm manner, one that impressed his teachers early on. And, like many in his generation, he had to learn to be the man of the house at a young age. In 1926, when Pete was just 14, his father died. Immediately, Pete knew his dreams of graduating high school would have to be cast aside so that he could provide for his family. He dropped out of the 8th grade and took a job delivering milk.

Four years went by. The Roaring 20s ended and 1930 came. It was only then that Pete finally got to go to high school, beginning as an 18-year-old freshman. He soon began playing on the basketball and boxing teams.

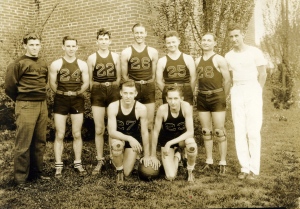

Below is Pete, second from the right, with the 1933 Corydon High School basketball team. His developed biceps give away the fact that he was four years older than his classmates.

Here is Pete as a student coach with the team. He’s the one in the sweater on the left.

Here is Pete as a student coach with the team. He’s the one in the sweater on the left.

In 1934, at age 22, Pete graduated high school.

In 1934, at age 22, Pete graduated high school.

A little over a year later, on August 1, 1935, Pete joined the Army. After basic training, he reported to Fort Knox, Kentucky, which was only a little over an hour’s drive from his hometown, and became a Private in Troop C of the First Cavalry Regiment.

A little over a year later, on August 1, 1935, Pete joined the Army. After basic training, he reported to Fort Knox, Kentucky, which was only a little over an hour’s drive from his hometown, and became a Private in Troop C of the First Cavalry Regiment.

Not long after he enlisted, he and his buddies went to a dance hall on a Saturday night. There, Pete’s life would change in an instant when he set eyes on a pretty brunette named Ruth. They talked, they danced, and at the end of the night, he asked if he could see her again. Her face fell and she shook her head no. “I’m not allowed to date until I’m sixteen,” she admitted. Having just turned fifteen, dating Pete would have to wait. Never one to be kept down for long, Pete waited and on the day Ruth turned 16, he appeared on Ruth’s doorstep and asked her on a date. He would never again look at another woman.

Pete took to military life and began to quickly move up the ranks. On December 7, 1937, he became an officer – Second Lieutenant James K. Stepro. In 1938, Pete left active duty and went into the reserves. Still hoping to better himself, he moved to Bloomington, Indiana to attend Indiana University. His schooling only lasted one year, though, because then, everything in Pete’s life changed.

By 1940, there were rumblings that America was going to go to war. Hitler was tearing across Europe and the Japanese were terrorizing Asia. As Hitler grew more powerful, the American military began to take counter measures. Pete’s reserve unit was activated on July 8, 1940. One week later, on July 15th, the 1st Armored Division was born and Pete’s regiment, the 1st Cavalry, became the 1st Armored Regiment. Later that same year, on December 14, he married Ruth.

Even with a wife waiting for him back home, Pete focused on his job. He was a natural leader and his men loved him. As he prepared for war, he continued to move up within the Army. In April of 1941, he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant.

After the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, America entered the war. Preparations to go oversees ramped up and 1942 found him in command of company H. Before he could be shipped overseas, Pete took one last weekend pass and went on a trip with his young wife.

Pete and Ruth:

After he returned from his trip with Ruth, Pete was moved to various posts around the US as training continued. He was promoted to Captain and not too long after, he was and on a ship to Northern Ireland.

After he returned from his trip with Ruth, Pete was moved to various posts around the US as training continued. He was promoted to Captain and not too long after, he was and on a ship to Northern Ireland.

Training in Ireland was intense. Pete was tasked with getting his men into fighting shape, teaching them to become one with the tanks they controlled. Just four months after arriving in Ireland, the 1st Armored Division moved to England and even closer to the action.

Below are several images of Pete in the UK for training:

On December 21, 1942, the 1st Armored Division would leave the UK to face the Axis powers for the first time. They were now in North Africa.

On December 21, 1942, the 1st Armored Division would leave the UK to face the Axis powers for the first time. They were now in North Africa.

By mid-January 1943, Pete and his men were seasoned veterans of the war. They had met with Hitler’s army on numerous occasions but so far, Company H had survived unscathed. Pete found time to write letters home, telling of how cold nights could be in the desert inside his tent (below).

One such letter, sent to Ruth on January 25, 1943, says:

One such letter, sent to Ruth on January 25, 1943, says:

North Africa Jan 25 (not sure)

Monday (I am sure)

Dearest Sweetheart Ruthie,

It has been sometime since I wrote to you, Jan. 17, I believe, and now I am going to take a few minutes to write to my sweet Ruthie. Hun, this morning I received two letters from you, one from Alfred, one from Robert. Since I last wrote to you I have received the following letters – Nov. 5, 27 – Dec. 13=14. The two this morning are Nov. 10-13. Hun, I am glad you have the letters dated because we have to destroy the address as soon as we receive a letter to keep it from falling in enemy’s hands. Also, a letter from Mom dated Nov. 27 – one from Robert Nov. 9, one from Doris Dec. 11.

Hun, you said you received a copy of the Illustrated London News. It has probably expired now since I subscribed for only a quarter of a year but I hope you renew the subscription.

Mom said that she is receiving an allotment from Robert so if she writes you to discontinue the $25 check, don’t discontinue it because I want her to save the money Robert has allotted – I mean save the $22 for him. This was the way I wrote him last summer (and your Petie knows his business.)

Ruthie, you can probably tell by the spots on the letter what kind of weather it is now. Your letter of Nov. 13 says, “We are shedding today and Ermel is helping Mother cook.” It should read “___ and I am helping Mother cook.” You had better learn, Honey-girl.

I suppose that by now Rodney has a new niece or nephew (maybe it’s a cousin) to play with.

Pretty soon it will be Feb. 1st. Time sure does fly. I would sure like to be home with you, Ruthie, then time wouldn’t matter so much.

Hun, I went to some old Roman or Carthaginian ruins and found a little clay tea pot. No telling how old it is, either. It has a picture of a little girl or boy engraved on it. The remains of the buildings have a lot of engravings just like the history books show. I couldn’t stay there but a couple of minutes and I would have liked a couple weeks to dig around in the ruins. It is hard to visualize those places as having been built centuries ago, and that those places were once great cities.

One day I took a ride on a camel – it had only one hump and it began to bubble inside. Lt. Horre said it was taking a drink from one of its several reservoirs.

Hun, I have a lots of figs and dates. Now I am in a big olive grove and there is a fig palm only 40 yards from me. They are good, too.

Last night I turned my radio on to BBC and heard the news from the US (not supposed to do this) and I heard them telling of things that are happening over here. It seems funny that the people at home know about what’s going on sooner than we do.

Hun, do you still have that Coca Cola on ice for me? You probably don’t think much of Cokes much in January. I am still wanting a big, juicy hamburger.

Ruthie, don’t let me forget to tell you about Lieut. Robertson’s slit trench when I get home. It happened some time ago when the planes first started their flying over us but it is still funny to me.

Have you been cracking any walnuts this winter? I would like be at home cracking them for you Rodney and Ila Sue would probably help us eat them. And we will have to teach Ila Sue the game we always played with Rodney, “going through a tunnel.” We liked that game, too, didn’t we?

Today is the 26th, Ruthie. If I get this letter in in time it may make good connections.

I think that I mentioned receiving Xmas cards from Masonic Lodge and Ladies Society Methodist Church.

I sent you several postcards from over here (not where I am) and I know you will like them if they arrive home.

Ruthie, Sweetheart, I must stup writing, but I will always keep loving you with all my heart. For always with loads of fun,

Your Captain Pete James K

After the letter was posted, Pete’s brief respite from the war was over and he went back to work.

Fighting intensified in late January and early February. On February 14, 1943, the 5th Panzer Army met up with three companies, including Pete’s, at Sidi bou Zid. Company H was first attacked by air and artillery shells soon followed. The fighting grew in intensity, chaos raining over Pete’s tank as they faced the Germans. Pete, ever the commander, stuck his head out of the turret so that he could direct the company. A shell hit the hatch cover, which caused Pete to look down at his men inside the tank to make sure that everyone was okay. Reassured, he popped his head back out into the open air. Seconds later, a German 88 artillery shell hit him directly, ending his life.

It wasn’t until February 20th, six days later, that Ruth was notified. She received this telegram while at her parents’ home.

THE SECRETARY OF WAR DESIRES ME TO EXPRESS HIS DEEP REGRET THAT YOUR HUSBAND, CAPTAIN JAMES K. STEPRO, WAS KILLED IN ACTION IN DEFENSE OF HIS COUNTRY IN THE NORTH AFRICAN AREA, FEB. 14. LETTER FOLLOWS. ADJUTANT GENERAL

Pete was buried far, far from home, first in a temporary resting place near the ancient ruins that he had excitedly written Ruth about.

Ruth was notified in June that Pete was to be posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Faid Pass. She was also presented with a Purple Heart for his valor at Sidi bou Zid.

Pete’s resting place wasn’t final until 1947. At that time, Ruth was notified that they were moving his body from the temporary cemetery to the North Africa American Cemetery at Carthage, Tunisia. She had the option of having his body sent home, but chose not to. There has always been some question as to why Ruth made that decision. It’s thought that she probably couldn’t endure the grief that would follow the arrival of his casket. By that time, four years had passed and the wounds, though still open, were no longer raw. Holding a funeral would have only opened them up, leaving her aching with heartbreak and drained all over again.

Pete’s resting place in Carthage, Tunisia:

I never knew Pete. And my father, who wrote a book about him (which provided me with the above details), never knew him either. Dad was born on May 7, 1945, just as Americans were celebrating the Victory in Europe. But Dad grew up hearing stories about Pete, and once he became a man and he, too, served in the armed forces, Pete’s widow, Ruth, began to give him some of Pete’s personal effects. I grew up staring at Pete’s Army boots, which were safely stored in a glass case, while Dad wove stories of Pete’s childhood and the people I knew who knew him. Just a few years ago, Dad gave me one of his caps, which very well might be the one he’s wearing here:

Even though I never got to have a single conversation with my great-great uncle, who would have been 66 when I was born, I am nonetheless moved by him. He was a strong, proud man full of honor, and he was one of the hundreds of thousands of Americans who gave their life in that most terrible of wars. And as my father advances in years, I feel it’s my duty to keep Pete’s memory alive. After what he did for me (and for the rest of the world), it’s the very least I can do for him.

Even though I never got to have a single conversation with my great-great uncle, who would have been 66 when I was born, I am nonetheless moved by him. He was a strong, proud man full of honor, and he was one of the hundreds of thousands of Americans who gave their life in that most terrible of wars. And as my father advances in years, I feel it’s my duty to keep Pete’s memory alive. After what he did for me (and for the rest of the world), it’s the very least I can do for him.

source – Pfeiffer, Larry. Captain Pete: A Biography of Captain James K. Stepro. Self-published. 1983.